Eccentric, macabre and surreal; in many ways, director Tim Burton is imbued with the spirit of an undeniably Gothic mad scientist. His instantly recognisable style includes classic Gothic conventions such as death, supernatural beings, Victorian aesthetics, and a dark yet often whimsical atmosphere. Although Burton’s work exists within the realm of classic Gothic, his films are simultaneously inspired by Gothic itself, not only operating under these conventions, but directly referencing other works of Gothic in an intertextual manner which situates him as an auteur of Postmodern Gothic. This is no more apparent than in his own versions of Mary Shelley’s seminal 1818 novel Frankenstein; Edward Scissorhands (1990)and Frankenweenie (2012). In Edward Scissorhands, Johnny Depp plays the titular creation; a man left with blades in place of hands after his inventor dies before finishing him, portraying him as an isolated outsider to the community that surrounds him, and ultimately casts him out. Although Edward Scissorhands is clearly influenced by Frankenstein, Burton’s black and white stop motion feature (a remake of his earlier short film) Frankenweenie is a more direct adaptation of Shelley’s novel. However, the monster created by young Victor is not a man brought back to life, but his beloved pet dog Sparky. Both of these films deal with the Gothic sensibility of creator and creation, the doubled outsider. However, unlike Shelley’s Victor, the creators in Burton’s films act with love and tenderness towards their so called ‘monsters’; thus, the real monster is ‘normal’ society itself, placing their own expectations of ‘monster’ onto these abject bodies. These tales thus align audience sympathies with the characters they should, in theory, fear, furthering this with representations of ‘mad scientists’ who are not necessarily obsessive or unethical, but rather eccentric creators with a genuine love for their creations, like Burton himself. Both Edward Scissorhands and Frankenweenie are also films which pay homage to classic Gothic fiction, with intertextual meshing encouraging audiences to further align themselves with the outsiders. And thus, it is argued that Burton situates himself as a Postmodern Gothic auteur by giving his stories a living heart, pumping new life into old tales.

The Seminality of The Modern Prometheus

Before exploring the subsequent works of Burton, it is crucial to discuss the novel not only highly influential to Burton, but to the Gothic itself; Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Since its publication in 1818, Frankenstein has taken on a life of its own, becoming woven into the very seams of popular culture. Of course, the story needs little explanation; Victor Frankenstein creates a man from various body parts, whom he proceeds to re-animate with dark consequences. Yet, the novel is far from simple, tackling themes such as science, life and death, and the idea of playing God, asking philosophical questions about human nature that still resonate today. Told from the perspective of Victor, Frankenstein helps to define the archetype of the mad scientist; a key figure within the Gothic tradition. Christopher P. Toumey specifically investigates this figure within the context of science, arguing that the mad scientist trope is one which suggests the immoral evils of science which disrupt the natural way of life. He states that these stories ‘describe which kinds of depraved people use science for amoral purposes and what becomes of them.’[1] Therefore, the mad scientist becomes an allegory for hubris, warning readers of the dangers they will face playing God. Toumey further contextualises this through Frankenstein, stating that characters such as Victor are scientists ‘who have been corrupted by knowledge.’[2] Frankenstein’s titular character thereby further acts as a cautionary tale of defying the natural order; however, these readings of the mad scientist trope do not recognise that at Frankenstein’s core, there is a story about rejection. In many examples of the mad scientist trope, most prominently in Frankenstein, the creator in question is often a parent-like figure to their creation. By giving life to his monster, Victor becomes its father; yet, he abandons the creature when he realises the immoral extent of his actions. However, as Henk Van Den Belt argues, it was not his act of creation that was immoral, rather ‘Frakenstein’s moral shortcoming was that he did not assume responsibility for his own creature and failed to give him the care he needed.’[3] Therefore, Frankenstein warns about the dangers of the absence of love just as much as it does of the abuse of science. Jason Scott Robert further asserts this, as he states ‘from this perspective, the lessons of Shelley’s story are about responsibility and cowardice, as Victor utterly abandons his creature.’[4] This is ultimately what causes the creature to turn murderous, as his loneliness and isolation turn him into a tragic figure rather than an inherently evil monster. This is apparent when the creature questions his existence, asking:

‘And what was I? Of my creation and creator I was absolutely ignorant; but I knew that I possessed no money, no friends, no kind of property. I was, besides, endued with a figure hideously deformed and loathsome; I was not even of the same nature as man […] When I looked around, I saw and heard of none like me. Was I then a monster, a blot upon the earth, from which all men fled, and whom all men disowned?’[5]

Thus, it is when the creature realises he will never be accepted that he becomes vengeful. As José Duarte and Ana Rita Martins state, ‘[Victor’s] creation is not the horrible, treacherous being Frankenstein deems him to be from the beginning. He effectively becomes the monster other characters expect him to be after being exposed to violent and cruel treatment.’[6] Therefore, there is the assertion that Victor is representative of a sense of ‘normality’ which rejects those who do not conform to societal standards. It is through a lack of love from Victor, the creature’s own father, that the creature becomes what he is expected to become; a monster.

A Creation of Love in Edward Scissorhands

Fig. 1: Edward is revealed to us as monstrous through his abject appearance.

The inevitable tragedy of Frankenstein’s creature is apparent in Tim Burton’s 1990 retelling of the story, Edward Scissorhands, wherein the titular protagonist fulfils the role of the creature. Like the monster, Edward is othered by his monster-like appearance, which marks him as the outsider to the town which is situated directly below the mansion in which he lives. This otherness is recognised by Maria Conecetta Constantini, who argues ‘people’s bodily characteristics significantly determine and legitimise their social identities.’[7] As seen in fig. 1,[8] when Edward is first revealed it becomes clear as to why he is isolated from the community; he has blades for hands. Although his uncanny appearance is frightening, when he interacts with Peg (the local Avon representative who finds him), he is timid; he reveals to her that his bladed hands are due to his creator, whom he refers to as his ‘father’,[9] dying. This is where his tragedy begins, as unlike Victor and his creature, Edward was not abandoned on purpose. Edward is naive and childlike, and thus, we can read the film in a similar way to Frankenstein; about a child that has lost a parent, in one way or another.

Fig. 2: Vincent imagines himself as Vincent Price, simultaneously becoming a mad scientist of sorts.

Edward’s creator, although with very little screen time, plays a significant role within the narrative, particularly when it comes to our reading of Edward. The creator was played by Vincent Price in his last role, which in itself holds massive significance towards the works of Burton. Price was hugely influential within the horror community, starring in many films inspired by classic Gothic fiction such as House on Haunted Hill (1959), House of Usher (1960), and The Last Man on Earth (1964). Thus, Price himself became an established horror icon, proving to be an influential figure over Burton’s own filmmaking. This is highly evinced in Burton’s stop motion short Vincent (1982), wherein a young boy, Vincent Malloy, dreams of being Vincent Price. In the film, he literally morphs into the actor (fig. 2),[10] playing out many of Price’s films in his imagination, even the mad scientist as shown. The film, narrated by Price, can clearly be interpreted as a story about Burton’s own childhood, inspired by classic horror works. However, the film is also an early example in Burton’s Postmodern Gothic sensibilities, through a meta-textual narrative about a real-life actor. As Maria Beville notes, Postmodern Gothic involves ‘the blurring of the borders that exist between the real and the fictional, which results in narrative self-consciousness and an interplay between the supernatural and the metafictional.’[11] This is proven through Vincent, as the film’s intertextuality references Gothic tropes, such as the mad scientist and laboratories, as well as Gothic auteurs, such as Edgar Allan Poe; the film even ends with the phrase ‘nevermore’ from Poe’s The Raven.[12] Thus, Vincent marks a starting point from which we can read Burton’s Postmodern Gothic influence.

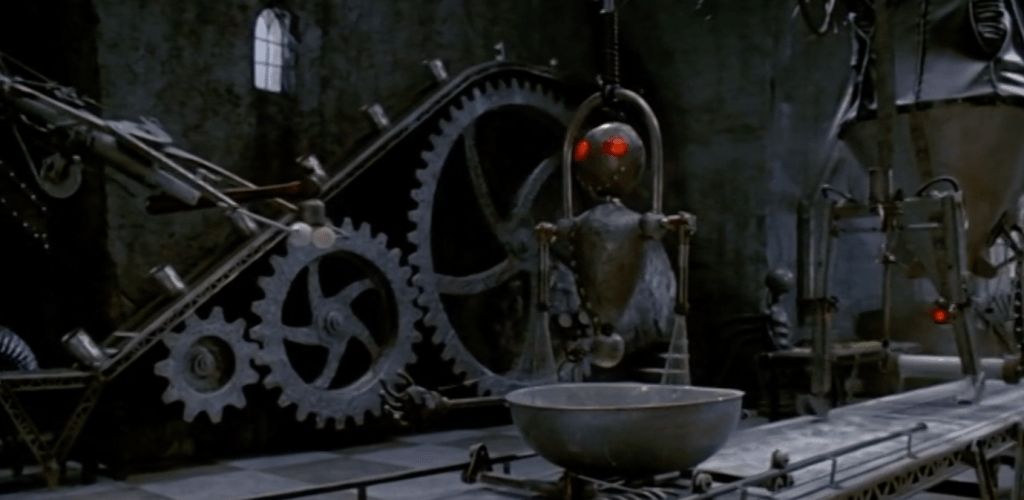

Fig. 3: Price’s inventors baking machine that marks him as a mad scientist.

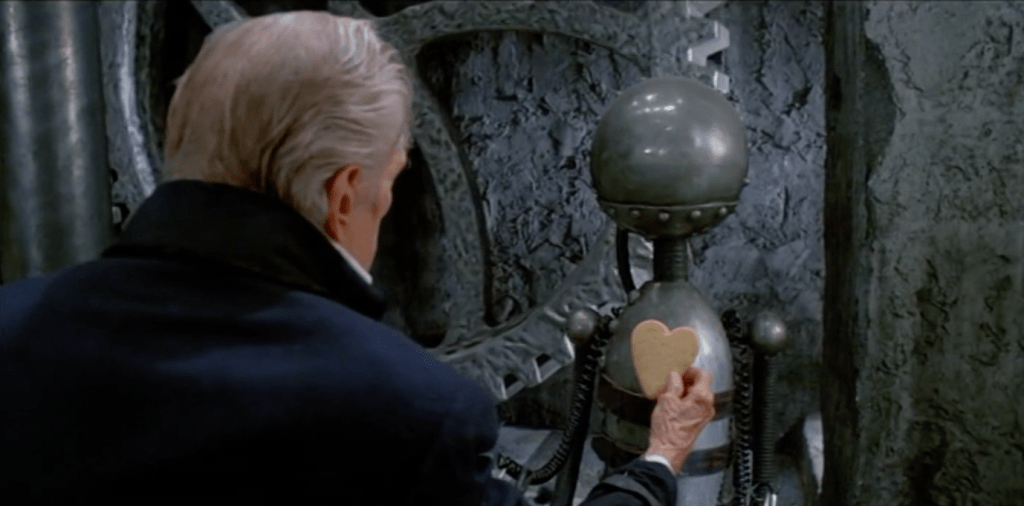

Fig. 4: Price’s scientist wants to create more than a robot; he wants to give his creations a heart.

Vincent therefore provides a clear lens as to the development of the creator within Edward Scissorhands. In a flashback scene where Price is introduced, we see a large baking machine (fig. 3);[13] it is mechanical and wholly unnatural, with the robots being formed like people. Yet, unlike the stereotypical trope where the mad scientist is uncaring and afraid of his creation, as is the case with Frankenstein, Price’s creator picks up a heart shaped biscuit, and holds it up to one of the robots, as seen in fig. 4.[14] There is the implication that Price’s creator is not immoral nor imbued with hubris; rather, his creation comes from a place of love. This is where Burton transforms Frankenstein; although we are encouraged to be somewhat sympathetic towards the creature, Frankenstein is portrayed in a more villainous nature, as it is his abandonment of his creation that leads to tragedy. Yet, here the creator is the opposite, being a loving and caring father figure towards Edward. Thus, when Edward is found by Peg, he is not grieving an abandoned father, but a dead one, and his pain does not turn him into a vengeful monster, but rather it makes him more human.

Therefore, as the film progresses, we see that it is not the creature’s creator that turns him into a monster, but the society that is portrayed as ‘normal’. During the climax of the film, Edward accidentally cuts his beloved Kim; however, Kim’s boyfriend is greatly angered by this, stating, ‘you can’t touch anything without destroying it.’[15] This, as Russell A. Porter argues, is Edward’s greatest tragedy of all, as he states ‘Edward’s hands, though, are not hands of fury but hands of desire, of a desire that inescapably wounds everything it embraces.’[16] Edward’s scissor hands mark his abject body as a sight of pain; pain from the grief of losing his father, the one who truly loved him. Apart from Kim and her family, the town then incites a mob against Edward, and as is the case with Frankenstein, he is banished to meet a tragic end. Yet, Edward is not killed, but rather his fate is isolation from a society who cannot accept him. Kim tells Edward ‘I love you’,[17] and thus, we are reminded that it is love that stops the creature from becoming monstrous. Edward does not become vengeful or evil, but rather love allows him to retain his humanness.

The Metatextual Scientist in Frankenweenie

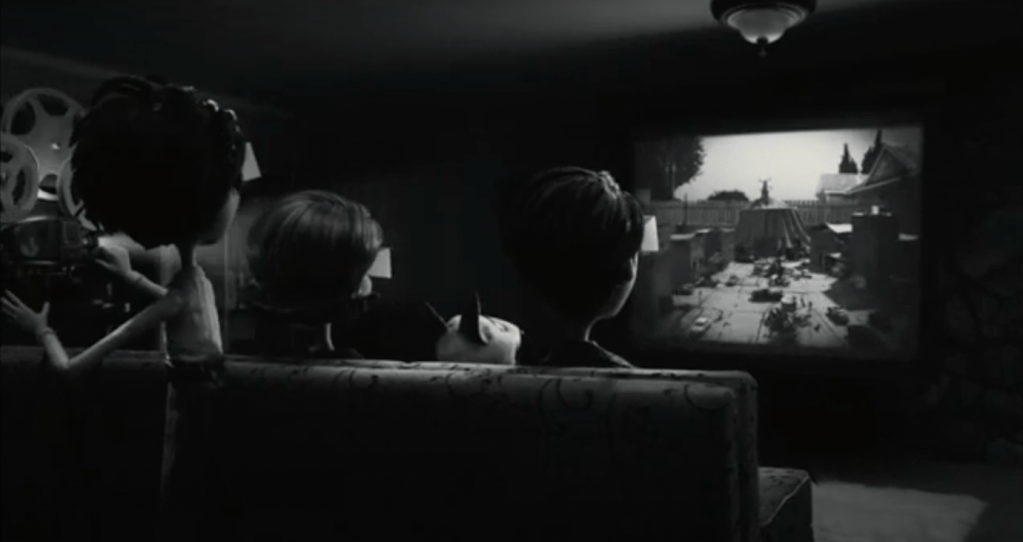

Fig. 5: Victor and his family watch his homemade monster movie implicating a sense of Gothic Postmodernism.

Although Edward Scissorhands focuses more on Frankenstein’s monster than the mad scientist himself, it still shows a crucial motif within Burton’s films wherein the mad scientist, or creator, is not afraid of their creations, but rather injected with the same spirit as them, and thus, they become one. This is realised through Burton’s later retelling of Frankenstein, Frankenweenie; a 2012 stop motion film inspired by Burton’s own live action film of the same name from 1984. Thus, Frankenweenie shows a similar pattern of self-referential Gothic as Edward Scissorhands; yet, Frankenweenie updates this model into a Gothic tale for children, dealing with similar themes of grief and isolation at a more childlike level. Rather than following the creature, Frankenweenie is more faithful to its original story as it follows the young Victor Frankenstein; an outsider interested in science, who resurrects his pet dog Sparky after he is hit by a car. Victor, like Vincent and Edward, is portrayed as somewhat of an outsider, which allows him to mould into the stereotype of mad scientist; for example, he would rather spend time at home with his dog than with his peers, interested more in science than socialisation. This is furthered through Edwards creative interest in filmmaking, which is seen from the opening of the film: the first scene is of a homemade film, ‘Monsters From Beyond’,[18] which immediately sets the tone of the film. The scene begins with this title card before zooming out to reveal Victor and his family watching the film, as seen in fig. 5.[19] This shot establishes that it is not only Victor’s own film that is in black and white, but also Frankenweenie, immediately suggesting an overt Gothic tone, which is used to remind viewers of classic Gothic tales from which Frankenweenie is inspired by. The act of movie-watching is also essential to the narrative of Frankenweenie, as the film is highly meta-textual of both Frankenstein and the classic monster movies inspired by such Gothic fiction. Frankenweenie is thus instantly marked as an example of Postmodern Gothic within its opening scene.

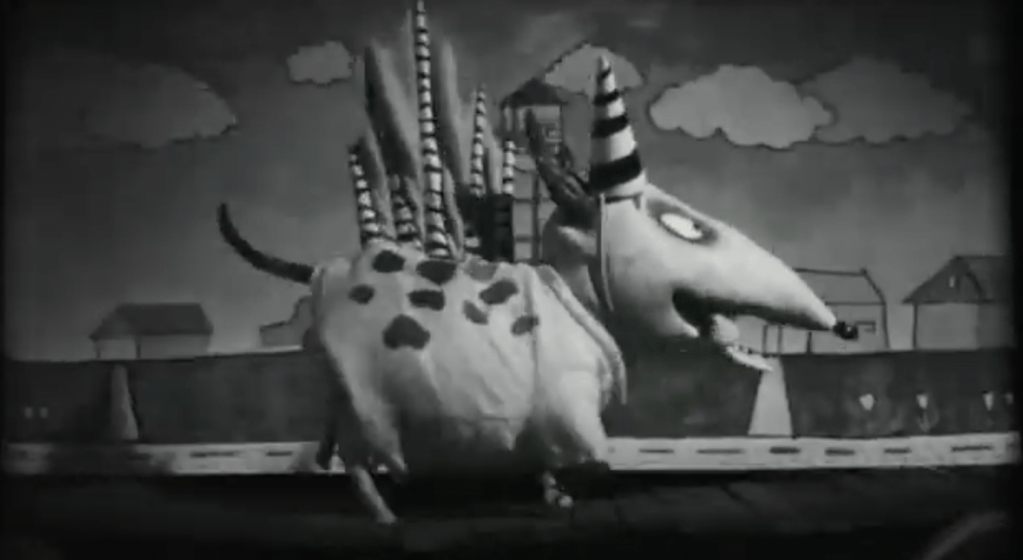

Fig. 6: Sparky in Victors film, foreshadowing his fate.

In fig. 6,[20] we see that Sparky is involved within Victor’s film, playing ‘sparkysaurus’, saving the day from the monster attack occurring. This crucially foreshadows Sparky’s role within the narrative, as he does indeed become a kind of hybridised monster like in Victor’s film. However, unlike his Frankenstein counterpart, we will go on to discuss how Sparky is in fact the hero of the story, allowing for a redemption of the tragic creature through love and care. Like Vincent from the short film of the same name, Victor in Frankenweenie can be read as an allegory for Burton himself, with him sharing a love of filmmaking and the macabre with the director. This is especially considered by Chris Louttit who states that ‘Burton grew up absorbed in a world of monster movies and B-pictures, experiencing these either at home on TV or in ‘weird triple bills’ at neighbourhood theatres in Burbank.’[21] Therefore, Burton’s intertextual meshing to create a Postmodern Gothic is prevalent, as he draws inspiration from the classic monster movie while directly referencing them in an attempt to pay homage. Thus, Burton continues to suggest the role of the outsider as a creative one, utilising their interest for good rather than evil. There is therefore the implication that the mad scientist is not immoral, but misunderstood; as Louttit further recognises about the mad scientists and creatures within these stories, ‘Burton always shows a great interest in their plight, and, it might even be suggested, identifies with them as a fellow ‘outsider’.’[22] Burton is thus interested in aligning audience sympathies with those who they are meant to fear, in an attempt to understand those labelled as ‘different’.

Fig. 7: The gremlin-like sea monkeys that terrorise the town.

Fig. 8: The Dracula inspired bat/cat fusion.

Fig. 9: The mummified hamster inspired by classic monsters of Hollywood.

As previously discussed, the mad scientist trope is often employed as a warning against the dangers of science gone wrong; a theme which is prevalent within Frankenweenie, however is subverted through a Postmodern lens to suggest it is not science itself that is the danger, but the intention behind such. Victor’s classmates learn of Sparky’s re-animation, and in an attempt to try and beat him at the science fair, they begin to re-animate their own pets as well, to disastrous consequences. The re-animated pets begin to attack the town’s funfair, taking on various roles of classic Gothic and Science Fiction; for example, the gremlin sea monkeys (fig. 7),[23] the bat which becomes fused with Sparky’s nemesis cat in order to create a vampiric feline (fig. 8),[24] and the mummified hamster (fig. 9).[25] These monsters are intertextual references to the famous Hammer horror monster movies made between the 1950s and 1970s, which were retellings of Gothic tales such as Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Referring back to the opening scene, the narrative transforms into one of Victor’s homemade movies, suggesting that it is he who understands this world and will thus have to be the one who saves it. It is Victor’s inherent ‘weirdness’ that allows him to overcome disaster, and rather than become the villain, helps to save the town alongside Sparky in a scene which reimagines Frankenstein’s own climax.

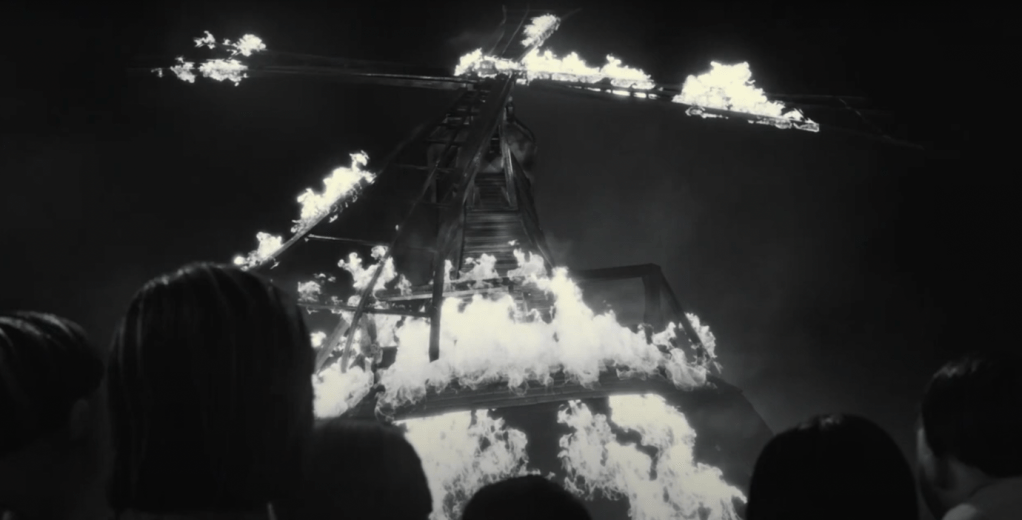

Fig. 10: The burning windmill, reminding audiences of Frankenstein, yet updating the story as Sparky is brought back to life.

Frankenweenie is similar to Edward Scissorhands in that it is not the creature’s own creator that turns against him but rather the society around him. The townspeople once again incite a mob which ends up at a burning windmill, seen in fig. 10.[26] When Sparky goes in to save Victor from the flames, he unfortunately dies once more in the fire, as the townspeople realise that he was not a monster, but a hero all along. They find Sparky’s body, and in a subversion of the Gothic tradition, the townspeople unite to bring Sparky to life again; this subversion is a key modernisation of the Gothic tradition, as the creature and scientist are no longer doomed to a tragic fate, but rather saved through love. Catherine Lester recognises that the form of a children’s film allows this ending, as she states ‘the theme of “acceptance” is identified in [children’s horror] and in subsequent examples of the subgenre, whether the acceptance of monsters, of other people, or of the consumption of the horror genre as a valid pastime for children.’[27] Unlike the original Victor Frankenstein, Frankenweenie’s Victor, and consequently his monster, are able to overcome their tragic fates through acceptance from the outside world. As Erin Hawley states: ‘Sparky is a reminder of the human preoccupation with death, loss, and the question of why (or whether, or when) we should abide by the laws of nature. Arguably, this indicates a re-imagining of the Frankenstein tale not only for child audiences but from a child’s perspective.’[28] Hawley’s suggestion of a childlike viewpoint is important for understanding Burton as a filmmaker, as he is able to instil the Gothic genre with a sense of whimsy and fantasy through a fresh lens, repositioning the monsters from the Gothic as tragic outsiders, whom the audience is therefore encouraged to empathise with.

Tim Burton – The Mad Scientist of Postmodern Gothic

Overall, Tim Burton re-animates the traditional Gothic tale of Frankenstein for a modern audience who understands how the Gothic operates, in order to show sympathy towards the misunderstood outcasts of society. Through Postmodern referencing of the classic Gothic tradition, Burton is able to utilise the genre to update it, putting his own spin on the stories in order to highlight the act of creation; whether that be scientifically or filmmaking. As Duarte and Martins state ‘Tim Burton possesses a very distinct style to the point that the adjective “Burtonesque” describes a specific cinematic world with its own imagery and rules’,[29] thus proving the inextricable link between the filmmaker and the worlds he builds. It is this link that allows him to explore the stories of the outsider as, in the words of Lydia from Beetlejuice, he himself is ‘strange and unusual.’[30] Weirdness is not a curse in the world of Burton, however, as it is shown to be the sight of wonder within the creative process, whether that is through Edward’s creators gentle spirit or Victor’s homemade monster movies. Thus, Burton awards the trope of the mad scientist with a heart, as they love their creations no matter how weird or terrifying they may be. This is therefore reflective of Burton’s own love towards the macabre, as he proves how the Gothic has inspired his work, influencing the creator he is today. Therefore, Burton himself becomes an intertextual figure; he is the mad scientist obsessed with investigating how the Gothic operates and how it has evolved over time, with his love re-animating stories with his own spark, giving them a new life.

Word Count: 3293

Bibliography

Beetlejuice, Dir. By Tim Burton, (Warner Bros., 1988)

Beville, Maria, ‘Chapter 1: Defining Gothic-Postmodern’, in Postmodern Studies,

(43), 2009, pp. 15-21, < https://login.napier.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fchapter-1-defining-gothic-postmodernism%2Fdocview%2F199165367%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D16607 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Constantini, Mariaconcetta, ‘Reconfiguring the Gothic Body in Postmodern Times:

Angela Carter’s Exposure of Flesh-Inscribed Stereotypes’, in Gothic Studies, Vol. 4 (1), 2002, pp. 14-27, < https://www-euppublishing-com.napier.idm.oclc.org/doi/abs/10.7227/GS.4.1.2 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Duarte José; Martins, Ana Rita, ‘“I don’t want him in my heart. I want him here with

me.”: On Tim Burton’s Frankenweenie (2012)’, in Hypercultura, Vol. 9, 2020, pp. 1-13, < http://litere.hyperion.ro/hypercultura/ > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Edward Scissorhands, Dir. By Tim Burton, (20th Century Studios, 1990), [Disney

Plus], < https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/browse/entity-3c963714-a9a8-4a80-9f29-44c659172b6f > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Frankenweenie, Dir. By Tim Burton, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2012),

[Disney Plus], < https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/browse/entity-1313be39-85f5-4808-b5b0-d4af93e665e4 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Hawley, Erin, ‘Re-imagining Horror in Children’s Animated Films’, in M/C Journal,

Vol. 18 (6), 2016, < https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1033 > [1/5/24].

Lester, Catherine, ‘The Children’s Horror Film: Characterizing an ‘Impossible’

Subgenre’, in The Velvet Light Trap, Vol. 78 (78), 2016, pp. 22-37, < http://dx.doi.org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.7560/VLT7803 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Louttit, Chris, ‘Tim Burton’s Pop-Victorian Gothic Aesthetic’, in Gothic Studies, Vol.20

(1-2), 2018, pp. 276-294, < https://doi-org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.7227/GS.0049open_in_new > [Date Accessed: 30/4/24].

Potter, Russell A., ‘Edward Schizohands: The Postmodern Gothic Body’, in

Postmodern Culture, Vol. 2 (3), 1992, pp. 1-14, < https://login.napier.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fedward-schizohands-postmodern-gothic-body%2Fdocview%2F1425513924%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D16607 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Scott Robert, Jason, ‘Rereading Frankenstein: What if Victor Frankenstein Had

Actually Been Evil?’, in The Hastings Center Report, Vol. 48 (6), 2018, pp. 21-24, < https://doi-org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/hast.933 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Shelley, Mary, Frankenstein, (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 1993)

Toumey, Christopher P., ‘The Moral Character of Mad Scientists: A Cultural Critique

of Science’, in Science, Technology, and Human Values, Vol. 17 (4), 1992, pp. 411-437, < https://www.jstor.org/stable/689735 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Van Den Belt, Henk, ‘Frankenstein Lives On’, in Science (American Association for

the Advancement of Science), Vol. 359 (6372), 2018, < https://www.jstor.org/stable/26401225 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

Vincent, Dir. By Tim Burton, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1982), [YouTube],

< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxQcBKUPm8o > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[1] Christopher P. Toumey, ‘The Moral Character of Mad Scientists: A Cultural Critique of Science’, in Science, Technology, and Human Values, Vol. 17 (4), 1992, pp. 411-437, p. 411, < https://www.jstor.org/stable/689735 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[2] Toumey, p. 415

[3] Henk Van Den Belt, ‘Frankenstein Lives On’, in Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), Vol. 359 (6372), 2018, p.137, < https://www.jstor.org/stable/26401225 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[4] Jason Scott Robert, ‘Rereading Frankenstein: What if Victor Frankenstein Had Actually Been Evil?’, in The Hastings Center Report, Vol. 48 (6), 2018, pp. 21-24, p. 21, < https://doi-org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/hast.933 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[5] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 1993), p. 93.

[6] José Duarte and Ana Rita Martins, ‘“I don’t want him in my heart. I want him here with me.”: On Tim Burton’s Frankenweenie (2012)’, in Hypercultura, Vol. 9, 2020, pp. 1-13, p. 4, < http://litere.hyperion.ro/hypercultura/ > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[7] Mariaconcetta Constantini, ‘Reconfiguring the Gothic Body in Postmodern Times: Angela Carter’s Exposure of Flesh-Inscribed Stereotypes’, in Gothic Studies, Vol. 4 (1), 2002, pp. 14-27, p. 14, < https://www-euppublishing-com.napier.idm.oclc.org/doi/abs/10.7227/GS.4.1.2 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[8] Edward Scissorhands, Dir. By Tim Burton, (20th Century Studios, 1990), [Disney Plus], < https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/browse/entity-3c963714-a9a8-4a80-9f29-44c659172b6f > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[9] Edward Scissorhands.

[10] Vincent, Dir. By Tim Burton, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1982), [YouTube], < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxQcBKUPm8o > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[11] Maria Beville, ‘Chapter 1: Defining Gothic-Postmodern’, in Postmodern Studies, (43), 2009, pp. 15-21, p. 15, < https://login.napier.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fchapter-1-defining-gothic-postmodernism%2Fdocview%2F199165367%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D16607 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[12] Vincent.

[13] Edward Scissorhands.

[14] Edward Scissorhands.

[15] Edward Scissorhands.

[16] Russell A. Potter, ‘Edward Schizohands: The Postmodern Gothic Body’, in Postmodern Culture, Vol. 2 (3), 1992, pp. 1-14, p. 1, < https://login.napier.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fedward-schizohands-postmodern-gothic-body%2Fdocview%2F1425513924%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D16607 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[17] Edward Scissorhands.

[18] Frankenweenie, Dir. By Tim Burton, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2012), [Disney Plus], < https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/browse/entity-1313be39-85f5-4808-b5b0-d4af93e665e4 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[19] Frankenweenie.

[20] Frankenweenie.

[21] Chris Louttit, ‘Tim Burton’s Pop-Victorian Gothic Aesthetic’, in Gothic Studies, Vol.20 (1-2), 2018, pp. 276-294, p. 283, < https://doi-org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.7227/GS.0049open_in_new > [Date Accessed: 30/4/24].

[22] Louttit, p. 287.

[23] Frankenweenie.

[24] Frankenweenie.

[25] Frankenweenie.

[26] Frankenweenie.

[27] Catherine Lester, ‘The Children’s Horror Film: Characterizing an ‘Impossible’ Subgenre’, in The Velvet Light Trap, Vol. 78 (78), 2016, pp. 22-37, p. 23, < http://dx.doi.org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.7560/VLT7803 > [Date Accessed: 1/5/24].

[28] Erin Hawley, ‘Re-imagining Horror in Children’s Animated Films’, in M/C Journal, Vol. 18 (6), 2016, < https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1033 > [1/5/24].

[29] Duarte and Martins, p. 5.

[30] Beetlejuice, Dir. By Tim Burton, (Warner Bros., 1988)

Leave a comment